How Long Does a Heart Stent Last?

Outline

– Understanding stents and what “longevity” actually means for devices and people

– How long a heart stent lasts: evidence, timelines, and typical risks

– Life expectancy after a stent: what changes, what doesn’t, and why

– What influences durability: patient, plaque, and procedure factors

– Putting it all together: ongoing care, warning signs, and key takeaways

Understanding Heart Stents and What “Longevity” Really Means

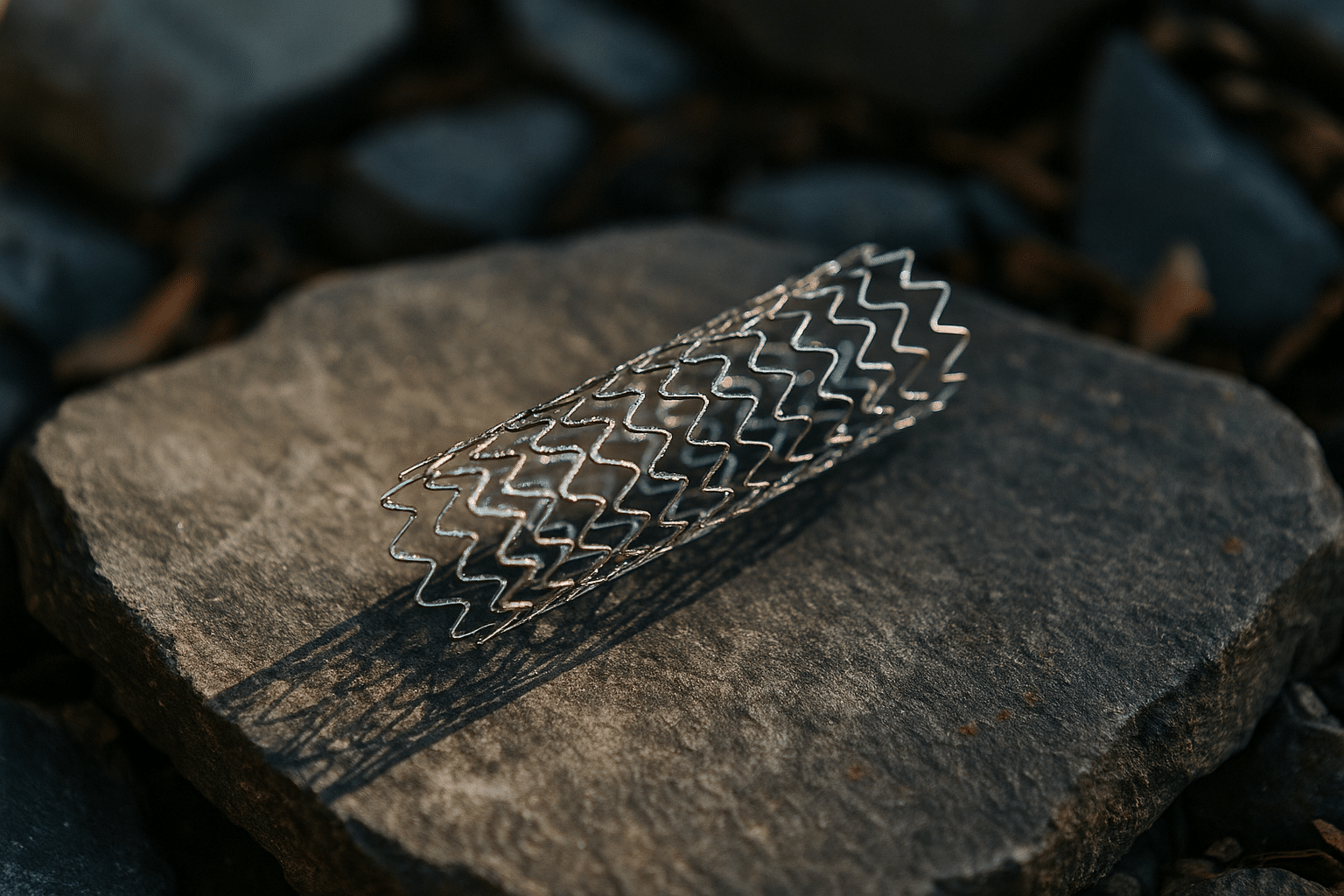

A heart stent is a tiny mesh scaffold placed inside a coronary artery to keep blood flowing when cholesterol plaque has narrowed the passage. It is not a replacement for the artery, and it does not “wear out” like a tire. Instead, it supports the vessel wall while your body heals. In emergencies such as a heart attack, a stent can restore flow quickly and limit heart muscle damage. In stable chest pain, a stent can reduce angina and improve exercise tolerance, while long‑term survival still depends on risk factors, medications, and lifestyle choices.

When people ask about stent longevity, two parallel clocks are running. One clock is the device: does the stent remain open, with smooth flow and without new blockage? The other clock is the person: how does overall heart health evolve over years and decades? These clocks are related, but not identical. Many individuals live for a long time with a well‑functioning stent because the device is designed to stay in place indefinitely. Yet a healthy life after stenting hinges on the larger picture: blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes, smoking status, fitness, and the health of other arteries that were never stented.

Modern stents come in several families. Bare‑metal stents, used more commonly in earlier years, are simple scaffolds. Drug‑eluting stents slowly release medication at the stented site to reduce tissue overgrowth and scarring, which can narrow the artery again. There are also specialized platforms, including bioresorbable scaffolds that gradually dissolve; these have niche roles and evolving evidence. The point is not that one category is universally superior for every situation, but that your interventional team selects a device to match the artery’s size, plaque features, and your medical profile. Longevity is therefore a function of good matching, precise placement, and attentive aftercare.

If you think of a stent as a support beam inside a tunnel, its job is to prevent cave‑ins where the tunnel was weak. The beam is strong, but the rest of the cave still matters. That is why discussions about “how long stents last” quickly broaden into how to maintain the whole coronary system—because your future is shaped more by the landscape than by the beam alone.

How Long Does a Heart Stent Last? Evidence, Timelines, and Real‑World Outlook

In everyday terms, a modern coronary stent is intended to be permanent. The metal framework of common drug‑eluting stents remains in the artery for life, while the drug coating is delivered over weeks to months. With bioresorbable scaffolds, the structure typically weakens and is absorbed over a few years. What most people truly want to know is the likelihood that the treated spot will stay open and symptom‑free. Contemporary data show that, with effective placement and medical therapy, the majority of patients do not need another procedure at the same spot in the first year, and many never do.

Two issues dominate durability: re‑narrowing (restenosis) and clotting inside the stent (stent thrombosis). Restenosis was relatively common with bare‑metal stents, affecting a notable share of patients within the first year. Drug‑eluting stents reduced this risk substantially, bringing typical repeat‑procedure rates at the treated site down to single‑digit percentages in many clinical settings. Stent thrombosis is less frequent but urgent; the highest risk window is the first weeks to months, which is why dual anti‑platelet therapy is prescribed. With adherence to medication and careful technique, the annual risk of very late stent thrombosis becomes quite low, though not zero.

Durability is also a matter of time horizons. Consider this simplified timeline that reflects common patterns reported across large studies:

– First 30 days: focus is on healing and preventing early clotting; risk is highest in this short window.

– One to 12 months: restenosis tends to declare itself if it is going to occur; many patients remain symptom‑free.

– Beyond one year: risk generally settles into a low, steady rate; new symptoms more often arise from disease in other segments rather than at the original stent site.

Because coronary artery disease can progress elsewhere, it is not unusual for long‑term follow‑up to address arteries that were never stented. This is why headlines that ask “Do stents last 10 years?” miss the nuance. The device usually remains, doing its job. Whether you need future procedures often depends on the rest of your coronary tree and the strength of your prevention plan. Many individuals report years of good function after stenting, and some sail through a decade or more without a return to the cath lab. Others need additional work because plaque biology and risk factors continue to challenge the system. The key is probability, not certainty—and probability improves with meticulous aftercare.

Life Expectancy After a Stent: What Changes, What Doesn’t, and Why

Stents are powerful at restoring flow, but they do not rewrite biology. In an acute heart attack, promptly opening the artery reduces heart muscle loss and is linked with better survival. In stable chest pain without high‑risk features, placing a stent relieves symptoms and can boost quality of life, while long‑term mortality remains driven primarily by aggressive risk‑factor control and medication. That is a crucial distinction: a stent treats a focal narrowing; your treatment plan addresses the disease process that caused it.

Think of life expectancy as a formula with multiple variables. Some are non‑modifiable, such as age and family history. Others are very much in your hands:

– Blood pressure: keeping it in a healthy range reduces strain on the artery wall.

– LDL cholesterol: lowering it curbs plaque growth; many high‑risk individuals aim for substantial reductions under medical guidance.

– Diabetes control: steady glucose levels protect vessels and microcirculation.

– Tobacco exposure: complete avoidance matters; even low‑level exposure is harmful.

– Fitness and weight: regular activity improves oxygen delivery, endothelial function, and mood.

Medication adherence is one of the most powerful levers. Dual anti‑platelet therapy prevents clotting while the stent heals; afterward, single anti‑platelet therapy and cholesterol‑lowering medication typically continue long term. Stopping these abruptly without clinician input can abruptly change risk, particularly in the early months. Cardiac rehabilitation, a supervised program of exercise and education, consistently improves outcomes and is associated with lower rehospitalization and better quality of life. People who complete it often describe increased confidence—the kind that helps you keep moving on days when motivation dips.

What about the long game? Many people live for decades after a stent. Outcomes vary by the extent of disease, heart pump function, kidney health, and how thoroughly risk factors are controlled. It is also common to discover that the artery segment with the stent remains fine years later, while a previously mild plaque elsewhere gradually matures. That pattern reinforces the message: your future is shaped more by system‑wide prevention than by the device itself. Regular follow‑up, clear communication with your care team, and early attention to any new symptoms knit together a pathway that supports a long and active life.

What Influences Stent Durability? Patient, Plaque, and Procedure

Several forces determine whether a stented artery segment stays smooth and open. First, patient biology matters. Diabetes, chronic kidney disease, smoking, and high LDL cholesterol promote inflammation and plaque activity, raising the chance of re‑narrowing. Systemic factors like poorly controlled blood pressure or sleep apnea can repeatedly stress vessel walls. Even infections and autoimmune conditions can nudge the endothelium toward dysfunction, tilting the balance toward scarring or clotting if not managed.

The plaque itself carries clues. Long, calcified, or very tight blockages are technically harder to treat, and small‑diameter vessels leave less room for error. Bifurcation lesions—where a side branch meets the main vessel—pose special challenges, sometimes requiring advanced techniques. The more complex the lesion, the more critical meticulous lesion preparation and stent sizing become. Good expansion and full apposition of the stent against the vessel wall reduce turbulence and help the lining regrow smoothly over the struts.

Procedure quality is another pillar. Contemporary practice often uses high‑resolution imaging inside the artery to confirm that the stent is fully expanded and well seated. That reduces the chance of early problems and supports long‑term patency. After placement, adherence to anti‑platelet therapy is essential while the inner lining heals over the stent. Missing doses in the early period can sharply increase the risk of clotting. Over the longer term, a consistent prevention plan slowly reshapes risk trajectories—the cumulative benefit of lower LDL, safe blood pressure, active living, and no tobacco is large.

Here is a practical way to think about the levers you and your team can pull:

– Clinical: accurate diagnosis, right stent choice, careful sizing, thorough expansion.

– Biological: cholesterol lowering, blood pressure control, diabetes management.

– Behavioral: medication adherence, smoke‑free living, regular exercise, restorative sleep, stress reduction.

– Monitoring: scheduled follow‑ups, timely response to symptoms, updated vaccinations to reduce infection‑related cardiac stress.

These layers work together. When they align, restenosis and thrombosis risks shrink, the stent fades into the background, and the rest of the coronary system enjoys calmer waters. The art of long‑term success is less about a single dramatic intervention and more about steady, cumulative wins.

Putting It All Together: Care Plan, Red Flags, and Key Takeaways

Once you leave the hospital, the road ahead is about consistency. Your clinician will usually prescribe dual anti‑platelet therapy for a period measured in months, sometimes up to a year depending on the procedure and your risk profile, followed by long‑term single anti‑platelet therapy. Cholesterol‑lowering medication, blood pressure control, and diabetes management anchor the medical plan. Do not change or stop these without guidance; early months are particularly sensitive. Cardiac rehabilitation, if offered, is worth the time. It delivers coaching, monitored exercise, and tailored education that speed recovery and reduce future events.

Day‑to‑day habits amplify the effect of medication:

– Eating pattern: emphasize vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, fish, and unsalted nuts; keep added sugars and ultra‑processed foods minimal.

– Movement: aim for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate activity, plus two sessions of light resistance work as cleared by your team.

– Sleep: target 7–9 hours; address snoring or pauses in breathing with evaluation if present.

– Stress: brief daily practices—breathwork, a walk, a journal—lower sympathetic surges that tighten arteries.

– Substances: avoid tobacco entirely and keep alcohol modest if you drink at all.

Know the red flags that warrant urgent help. New or escalating chest pressure, shortness of breath at rest, pain radiating to the jaw, neck, back, or arm, sudden cold sweats, or fainting are reasons to seek emergency evaluation. Call local emergency services rather than driving yourself. For nonurgent questions—like how to handle a dental procedure while on anti‑platelet therapy—ask in advance; your team can coordinate timing and precautions. Most modern stents are compatible with magnetic resonance imaging under specified conditions; share your implant details with the imaging center so they can verify safety.

Conclusion—your outlook in one paragraph: A stent is a durable scaffold, often serving quietly for years while the real work happens in your daily choices. Most people can expect excellent symptom relief and a low likelihood of repeat procedures at the original site after the first year, especially with steady medication and prevention. Life expectancy after stenting depends less on the metal in the artery and more on the system it supports. Keep your appointments, take the pills, move your body, and mind the signals; that steady cadence is how you turn a single procedure into a long, active chapter.